We know classical theory fails to explain nature – and such a failure is historically linked to the birth of quantum theory. Initially a controversial theory, with features that consistently defy our classical intuition, has nevertheless passed every experimental test to date. So, we can say it is a successful description so far. However, can we be sure that nature is really described by quantum theory? Is it possible (or even likely) that nature is actually not quantum and we just fail to see it? What guarantees that nature is not even crazier than the picture painted by quantum theory?

Indeed, recent paradoxes – such as Wigner’s friend-type gedankenexperiments1 – show that quantum theory might be inconsistent with some natural principles. Together with the incompatibility with general relativity, this raises doubt on the idea that quantum theory may never be dropped by a different description of natural phenomena. As scientists, we must be open to the possibility that the current paradigm may be flawed (historically, this is the rule!). So, if something surpasses quantum theory, what would that be? How to approach this problem?

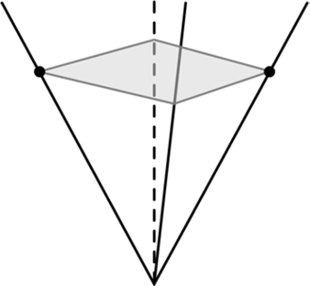

It is clear that, to tackle the above questions, we would profit from an approach that focuses on operational aspects (probabilities!) and which is independent from the quantum structure. The generalized probabilistic theories (GPTs) framework provides one such approach: built from fundamental concepts, it considers a simple mathematical structure to describe states, transformations and measurements in real vector spaces. Both classical and quantum theories are examples of GPTs, but many more general theories can be constructed which allow for even crazier behaviours than those described by quantum theory. For instance, a GPT called “Boxworld” can reproduce maximal violations of Bell inequalities2; more recently, a theory called ‘Witworld’ allows us to describe post-quantum steering!3 Thus, one can see that the GPT framework provides a vast stage to analyze operational theories, being a nice tool to explore unknown grounds without necessarily committing to the quantum formalism4.

The GPT approach, however, is useful not only to speculate about weird (and possibly never seen) phenomena. It also allows us to understand how a physical principle might impact operational descriptions. For instance, treating the different ways to encode classical information on the same level may lead to the strong duality between states and measurements observed in quantum theory (and other GPTs!)5. Requiring non-trivial transformations, such as those allowing for classical computation, may rule out strongly nonlocal theories, such as “Boxworld”6.

Even if you believe quantum theory will beat every obstacle and remain a good theory to explain natural phenomena, the GPT approach is also worthy. It provides alternative means to understand quantum theory itself even better: for instance, by studying not only how the quantum departs from the classical, but also analyzing why it is not “more” nonclassical. The GPT framework also contributed to reconstructions of quantum theory from physical principles7,8, as opposed to the usually ad-hoc textbook formulation of quantum mechanics.

From an opposite perspective, a desirable principle to impose on such crazy theories is to conciliate them with our day-by-day classical experience9,10. Recently, we have been dedicating efforts to this problem, giving descriptions of Darwinism processes in GPTs11 and studying how noncontextuality may emerge in noisy scenarios.

There are many more routes to take with the GPT approach, which, almost certainly, will teach us a lot about possible descriptions of nature. If you’re interested in taking such paths with us, do not hesitate to contact!

References

-

D. Frauchiger, R. Renner, Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself, Nature Communications volume 9, Article number: 3711 (2018) J. Barrett, Information processing in generalized probabilistic theories , arXiv:quant-ph/0508211.

-

P. J. Cavalcanti, J. H. Selby, J. Sikora, T. D. Galley, A. B. Sainz, Witworld: A generalised probabilistic theory featuring post-quantum steering, arXiv:2102.06581.

-

M.P. Müller, J. Oppenheim, O. C. O. Dahlsten, The black hole information problem beyond quantum theory, Journal of High Energy Physics article number 116 (2012).

-

D. Gross, M. P. Müller, R. Colbeck, and O. C. O. Dahlsten. All reversible dynamics in maximally nonlocal theories are trivial. Phys. Rev. Lett., 104:080402, 2010.

-

M.P. Müller, C. Ududec, Structure of reversible computation determines the self-duality of quantum theory. Phys. Rev. Lett., 108:130401, 2012.

-

M. P. Müller. Probabilistic theories and reconstructions of quantum theory. Les Houches 2019 lecture notes, arXiv:2011.01286, 2020. arXiv:2011.01286 and references therein, in particular:

-

L. Hardy, Reconstructing Quantum Theory arXiv:1303.1538.

-

J. G. Richens, J. H. Selby, and S. W. Al-Safi. Entanglement is necessary for emergent classicality in all physical theories. Phys. Rev. Lett., 119:080503, 2017.

-

C. M. Scandolo, R. Salazar, J. K. Korbicz, and P. Horodecki. The origin of objectivity in all fundamental causal theories. arXiv:1805.12126.

-

R. D. Baldijão,M. Krumm,A. J. P. Garner, M. P. Müller, Quantum Darwinism and the spreading of classical information in nonclassical theories, arXiv:2012.06559.