When we classically think about probabilities, we usually consider that random variables have “possibly well-defined values”, which are random simply because we don’t know every detail about them. In other words, we usually consider all possible definite values and simply weight them according to some rule or our previous knowledge. The same applies to joint probabilities, i.e. probabilities for more than one random variable.

Now imagine a collection of random variables and a choice of subcollections that will be jointly tested. Classically, whenever we have a consistent description for all those subcollections, we take for granted that there is also a description for the full collection, which generates the descriptions for each subcollection by marginalisation, i.e. the process of summing on the ignored variables. Contextuality appears when there is no consistent description of the whole!

Let us discuss one example: consider three random variables, X1,X2,X3, assuming values 0 or 1, each. However, we are only allowed to test them two by two… Consider that, whenever you test any two variables, they always disagree (one is 0, the other is 1). Is it clear that there is no way of consistently attaching definite values to the three variables in a way that this “anti-correlation” manifests itself? This is similar to what people call frustration in magnetism and the liar cycle in logic. This example was also studied by George Boole, himself, in 19th century.

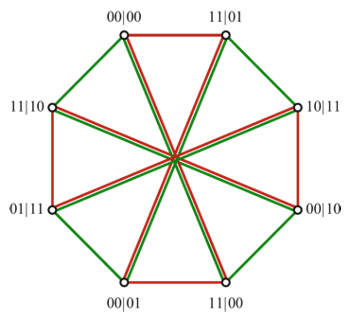

The previous example has no direct relation to quantum theory. However, we can generalise it, e.g., to five random variables, X1,X2,X3,X4,X5, assuming values 0 or 1, each, with the restriction that we can only test neighbours Xi,Xi+1, where X1 and X5 are also neighbours. We can consider this example as a game: consider that whenever you choose a pair of neighbours and their results are opposite, you win one point, while if they are equal, you lose one point. With definite values for all variables, you can build configurations where four neighbour pairs disagree, but the fifth necessarily agrees, giving a pay off of 3/5. Quantum theory allows us to do better than this, reaching a pay off cos(π/5)>0.8. This is an example of quantum contextuality.

One nice way of studying contextuality is using non-contextuality inequalities, which are analogous to Bell inequalities, under the classical assumption of non-contextuality. This also brings an interesting geometric flavour to such study, where describing interesting sets of behaviours is one of our targets.

Our group has made many contributions to this theme, including papers, books, and thesis.